Flowers for Agernon Why Did Charlie Become Dumb Again

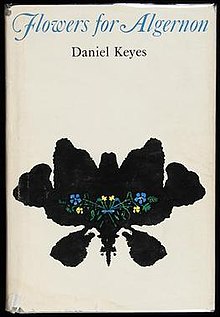

Start edition embrace | |

| Writer | Daniel Keyes |

|---|---|

| Land | United states |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | Harcourt, Brace & World |

| Publication engagement | April 1959 (brusk story) March 1966 (novel) |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 311 (novel)[1] |

| ISBN | 0-fifteen-131510-8 |

| OCLC | 232370 |

Flowers for Algernon is a curt story by American writer Daniel Keyes, after expanded by him into a novel and subsequently adjusted for film and other media. The curt story, written in 1958 and beginning published in the Apr 1959 issue of The Mag of Fantasy & Scientific discipline Fiction, won the Hugo Award for Best Short Story in 1960.[2] The novel was published in 1966 and was joint winner of that yr's Nebula Award for All-time Novel (with Boom-boom-17).[3]

Algernon is a laboratory mouse who has undergone surgery to increment his intelligence. The story is told past a series of progress reports written by Charlie Gordon, the kickoff man subject field for the surgery, and it touches on ethical and moral themes such every bit the treatment of the mentally disabled.[iv]

Although the volume[v] has often been challenged for removal from libraries in the United States and Canada, sometimes successfully, it is frequently taught in schools around the world and has been adapted many times for television, theater, radio and as the Academy Award-winning film Charly.[6] [seven] [8]

Groundwork [edit]

The ideas for Flowers for Algernon adult over fourteen years and were inspired by events in Keyes'southward life, starting in 1945 with Keyes's conflict with his parents, who were pushing him through a pre-medical education despite his desire to pursue a writing career. Keyes felt that his education was driving a wedge between himself and his parents, and this led him to wonder what would happen if information technology were possible to increase a person'southward intelligence.[4] [viii] [ix]

A pivotal moment occurred in 1957 while Keyes was didactics English to students with special needs; one of them asked him if information technology would be possible to be put into an ordinary class (mainstreamed) if he worked difficult and became smart.[four] [10] Keyes also witnessed the dramatic modify in another learning-disabled student who regressed after he was removed from regular lessons. Keyes said that "When he came back to school, he had lost it all. He could not read. He reverted to what he had been. Information technology was a heart-breaker."[four]

Characters in the book were based on people in Keyes'south life. The character of Algernon was inspired by a university autopsy class, and the name was inspired by the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne.[11] [ meliorate source needed ] Nemur and Strauss, the scientists who develop the intelligence-enhancing surgery in the story, were based on professors Keyes met while studying psychoanalysis in graduate school.[xi] [ ameliorate source needed ]

In 1958, Keyes was approached by Galaxy Science Fiction magazine to write a story, at which point the elements of Flowers for Algernon fell into identify.[11] [ better source needed ] When the story was submitted to Galaxy, however, editor Horace Gold suggested irresolute the ending so that Charlie retained his intelligence, married Alice Kinnian, and lived happily ever after.[12] Keyes refused to brand the change and sold the story to The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction instead.[eleven] [ ameliorate source needed ]

Keyes worked on the expanded novel between 1962 and 1965[thirteen] and showtime tried to sell it to Doubleday, merely they also wanted to change the ending. Again, Keyes refused and gave Doubleday back their accelerate.[12] Five publishers rejected the story over the grade of a year[12] until it was published past Harcourt in 1966.

Publication history [edit]

The short story "Flowers for Algernon" was first published equally the lead story in the April 1959 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction.[11] [ better source needed ] It was later reprinted in The All-time from Fantasy and Scientific discipline Fiction, 9th series (1960),[14] the Fifth Annual of the Year's Best Science Fiction (1960),[xv] Best Articles and Stories (1961),[sixteen] [ improve source needed ] Literary Cavalcade (1961),[16] [ ameliorate source needed ] The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One, 1929–1964 (1970),[17] and The Mag of Fantasy & Science Fiction: A thirty-Yr Retrospective (1980).[14]

The expanded novel was beginning published in 1966 by Harcourt Brace with the Bantam paperback post-obit in 1968.[sixteen] [ better source needed ] Equally of 1997[update] the novel had not been out of print since its publication.[12] By 2004, it had been translated into 27 languages, published in 30 countries and sold more than 5 million copies.[xviii] [ better source needed ]

Synopsis [edit]

The short story and the novel share many similar plot points, but the novel expands significantly on Charlie'due south developing emotional state too equally his intelligence, his memories of childhood, and the relationship with his family unit. Both are presented as a serial of periodical entries ("progress reports") written by the protagonist, Charlie Gordon. The style, grammer, spelling, and punctuation of these reports reflect changes in his mental and emotional growth.

Short story [edit]

Charlie is a man with an IQ of 68 who works a menial job as a janitor and delivery person at Donnegan's Plastic Box Company. He is selected to undergo an experimental surgical technique to increase his intelligence. The technique had already been tested on a number of animals; the great success was with Algernon, a laboratory mouse. The surgery on Charlie is also a success, and his IQ triples.

He realizes his co-workers at the mill, who he idea were his friends, only liked having him around so they could tease him. His new intelligence scares his co-workers, and they start a petition to accept him fired, only when Charlie learns almost the petition, he quits. Equally Charlie's intelligence peaks, Algernon's suddenly declines—he loses his increased intelligence and mental historic period, and dies afterward, cached in the dorsum yard of Charlie's abode. Charlie realizes his intelligence increase is likewise temporary. He begins researching to find the flaw in the experiment, which he calls the "Algernon–Gordon Effect". When he finishes his piece of work, his intelligence regresses to its original country. Charlie is aware of, and pained past, what is happening to him every bit he loses his knowledge and his ability to read and write. He resumes his old job every bit a janitor at Donnegan's Plastic Box Company and tries to get dorsum to how things used to exist, but he cannot stand the pity from his co-workers, his landlady, and Ms. Kinnian. Charlie states he plans to "go abroad" from New York. His final wish is for someone to put flowers on Algernon's grave.

Novel [edit]

The novel opens with an epigraph taken from Volume VII of Plato's The Republic:

Anyone who has common sense volition remember that the bewilderments of the center are of two kinds, and arise from 2 causes, either from coming out of the light or from going into the light, which is true of the mind'southward eye, quite as much as of the bodily eye.

Charlie Gordon, 32 years old, demonstrates an IQ of 68 due to untreated phenylketonuria. His uncle has arranged for him to hold a menial job at a bakery and so that he will non have to alive at the Warren State Dwelling house and Training Schoolhouse, a state institution. Desiring to amend himself, Charlie attends reading and writing classes, taught by Miss Alice Kinnian, at the Beekman College Middle for Retarded Adults. Two researchers at Beekman, Professor Nemur and Dr. Strauss, are looking for a human exam subject on whom to endeavor a new surgical technique intended to increment intelligence. They take already performed the surgery on a mouse named Algernon, resulting in a dramatic improvement in his mental functioning. Based on Alice'south recommendation and his motivation to ameliorate, Nemur and Strauss choose Charlie over smarter pupils to undergo the procedure.

The functioning is successful, and inside the adjacent three months Charlie'due south IQ reaches 185. At the aforementioned fourth dimension, he begins recalling his childhood and remembers that his female parent Rose physically abused him and wasted coin on false treatments for his disability, while his younger sister Norma resented him. As Charlie'south intelligence, education, and agreement of the globe increment, his relationships with people deteriorate. His co-workers at the baker, who used to amuse themselves at his expense, at present fright and resent his increased intelligence and persuade his boss to fire him. Alice enters a relationship with Charlie just breaks upward with him later she realizes she can no longer relate to him and claims his intelligence has inverse his personality. Later, Charlie loses trust in Strauss and, particularly, Nemur, believing that they considered him a laboratory discipline and non man before the operation. While at a scientific convention in Chicago, Charlie feels humiliated when he is treated similar an experiment and, in retaliation, flees with Algernon.

After moving to Manhattan with Algernon, Charlie becomes involved in a relationship with Fay Lillman, his neighbor, to sate his loneliness. Later an incident with a disabled bus boy Charlie becomes inspired to keep and amend Nemur and Strauss'due south experiment and applies for a grant. However, he notices Algernon is commencement to deport erratically. Throughout his research, he discovers a flaw behind Nemur and Strauss'due south procedure indicating that he will lose his intelligence and, possibly, regress back to a primitive state. While still holding onto his intelligence, Charlie publishes his findings as the "Algernon–Gordon effect", as Algernon dies.

As Charlie begins to regress to his sometime mental state, he finds closure with his family. Rose, who still lives in the family'southward onetime dwelling in Brooklyn, has developed dementia and recognizes him only briefly; his begetter Matt, who bankrupt off contact with the family unit years earlier, does not recognize him at all. He is only able to reconnect with Norma, who is now caring for Rose in their newly depressed neighborhood, but declines to stay with them. Charlie begins dating Alice again, but his frustration with losing intelligence eventually causes him to end his relationships with her and Dr. Strauss. Unable to bear the thought of existence dependent and pitied by his friends and co-workers, he decides to live at the Warren State Habitation and Grooming School, where no 1 knows about the operation. In a final postscript to his writings, he requests that someone put flowers on Algernon'south grave in the backyard of Charlie'due south erstwhile residence.

Mode [edit]

Both the novel and the short story are written in an epistolary style collecting together Charlie'due south personal "progress reports" from a few days earlier the operation until his terminal regression. Initially, the reports are filled with spelling errors and awkwardly constructed sentences.[nineteen] Post-obit the performance, however, the reports begin to show marked improvements in spelling, grammar, punctuation, and diction, indicating a rise in his intelligence.[20] Charlie's regression is conveyed by the loss of these skills.[20]

Themes [edit]

Of import themes in Flowers for Algernon include the treatment of the mentally disabled,[4] [21] the impact on happiness of the conflict between intellect and emotion,[22] [23] and how events in the past can influence a person subsequently in life.[23] Algernon is an example of a story that incorporates the science-fiction theme of uplift.[24]

Reception [edit]

Algis Budrys of Galaxy Science Fiction praised Flowers for Algernon 's realistic depiction of people equally "rounded characters". Stating in Baronial 1966 that Keyes had published little fiction and whether he would publish more was unknown, he concluded "If this is a beginning, and so what a beginning it is, and if it is the high point in a very short career, and so what a career".[25] In February 1967 Budrys named the book the best novel of the year.[26]

Awards [edit]

The original brusk story won the Hugo Honor for Best Curt Story in 1960.[2] The expanded novel was joint winner of the Nebula Laurels for Best Novel in 1966, tied with Babel-17 by Samuel R. Delany,[3] and was nominated for the Hugo Award for Best Novel in 1967, losing out to The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress past Robert A. Heinlein.[27]

In the tardily 1960s, the Scientific discipline Fiction Writers of America (SFWA) decided to requite Nebula Awards retroactively and voted for their favourite science fiction stories of the era catastrophe Dec 31, 1964 (before the Nebula Award was conceived). The short story version of Flowers for Algernon was voted tertiary out of 132 nominees and was published in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume I, 1929–1964 in 1970.[28] Keyes was elected the SFWA Author Emeritus in 2000 for making a significant contribution to science fiction and fantasy, primarily equally a outcome of Flowers for Algernon.[29]

Censorship [edit]

Flowers for Algernon is on the American Library Association's list of the 100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–1999 at number 43.[half dozen] The reasons for the challenges vary, but normally eye on those parts of the novel in which Charlie struggles to understand and express his sexual desires.[30] [ better source needed ] Many of the challenges accept proved unsuccessful, but the book has occasionally been removed from school libraries, including some in Pennsylvania and Texas.[31] [ better source needed ]

In January 1970, the schoolhouse board of Cranbrook, British Columbia, as well equally Calgary, Alberta, removed the Flowers for Algernon novel from the local historic period 14–15 curriculum and the school library, after a parent complained that it was "filthy and immoral". The president of the British Columbia Teachers' Federation criticised the action. Flowers for Algernon was part of the British Columbia Department of Educational activity list of canonical books for grade nine and was recommended by the British Columbia Secondary Clan of Teachers of English. A month after, the board reconsidered and returned the book to the library; they did not, all the same, lift its ban from the curriculum.[32] [33]

Inspiration [edit]

Flowers for Algernon has been the inspiration for works that include the album A Curious Feeling by Genesis keyboardist Tony Banks.[34] It also inspired the 2006 modern dance work Holeulone past Karine Pontiès, which won the Prix de la Critique de la Communauté française de Belgique for all-time trip the light fantastic piece.[35] A 2001 episode of the Television receiver series The Simpsons titled "HOMR" has a plot similar to the novel.[36] A 2013 episode of the TV series It's Ever Sunny in Philadelphia titled "Flowers for Charlie" is heavily based on the novel.[37] The proper name Algernon inspired the author Iain Cameron Williams to create his poetic piece of work The Empirical Observations of Algernon [38] after Williams's father had nicknamed him Algernon as a teenager (taken from Flowers for Algernon) due to his son's highly inquisitive nature.[39]

Adaptations [edit]

Flowers for Algernon has been adapted many times for dissimilar media including phase, screen, and radio. These adaptations include:

- A 1961 episode of the tv set drama The United States Steel Hour, "The Ii Worlds of Charlie Gordon", starring Cliff Robertson.[40] [41]

- A 1968 picture show, Charly, also starring Cliff Robertson, for which he won the Academy Honor for Best Thespian.[40] [42]

- A 1975 phase play, Entaha El-Dars Ya Ghabi (The Lesson is Over, Stupid) by Egyptian histrion Mohamed Sobhi

- A 1969 stage play, Flowers for Algernon past David Rogers.[40] [43]

- A 1978 stage musical, Charlie and Algernon by David Rogers and Charles Strouse.[forty] [44] [45]

- A 1979 stone opera, A Curious Feeling by Tony Banks.[46]

- A 1991 radio play, Flowers for Algernon, for BBC Radio 4 starring Tom Courtenay.[47]

- A 2000 television film, Flowers for Algernon, starring Matthew Modine.

- A 2001 episode of the television series The Invisible Man, "Flowers for Hobbes".

- A 2001 Spider-Human comic story, "Flowers for Rhino", by Peter Milligan and Duncan Fregredo.

- A 2002 Japanese drama, Algernon ni Hanataba o for Fuji Television, starring Yūsuke Santamaria.

- A 2006 French television film, Des fleurs pour Algernon.

- A 2013 episode of the television receiver series Information technology's Always Sunny in Philadelphia, "Flowers for Charlie".

- A 2015 Japanese drama, Algernon ni Hanataba o for Tokyo Broadcasting System, starring Yamashita Tomohisa and Chiaki Kuriyama.

- A 2020 episode of the television series Adjourn Your Enthusiasm, "Beep Panic".

Further stage and radio adaptations take been produced in French republic (1982), Republic of ireland (1983), Australia (1984), Poland (1985), Japan (1987, 1990), and Czechoslovakia (1988).[40]

References [edit]

- ^ Daniel Keyes (1966). Flowers for Algernon (1st ed.). New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. OCLC 232370.

- ^ a b 1960 Hugo Awards, TheHugoAwards.org, July 26, 2007, retrieved Apr 23, 2008

- ^ a b "Past Winners of SWFA Nebula Awards". Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- ^ a b c d due east Emily Langer (June 18, 2014). "Daniel Keyes, author of the classic book 'Flowers for Algernon,' dies at 86". The Washington Post.

- ^ Daniel Keyes (2004) [1966]. Flowers for Algernon. Orlando: Harcourt. ISBN9780156030304. OCLC 0156030306.

- ^ a b The 100 Nigh Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–1999 -ALA.org

- ^ Kyle Munley (Oct 3, 2008). "Challenged and Banned: Flowers for Algernon". Suvudu. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- ^ a b "Frequently Asked Questions and Updates". Daniel Keyes. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ^ Keyes 1999, p. xvi

- ^ Keyes 1999, p. 97

- ^ a b c d east Hill 2004, p. 3

- ^ a b c d "Daniel Keyes: xl Years of Algernon". Locus Magazine. June 1997. Retrieved Apr 23, 2008.

- ^ Bujalski 2002, p. 52

- ^ a b "Fantasy & Science Fiction: Anthology Stories (by author)". sfsite.com. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

- ^ "The 5th Almanac of the Year'southward All-time SF. Judith Merril. Simon & Schuster 1960". bestsf.net. Archived from the original on March 16, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

- ^ a b c Hill 2004, p. three

- ^ Silverberg 1970

- ^ Loma 2004, p. 9

- ^ Bujalski 2002, p. 21

- ^ a b Bujalski 2002, p. 15

- ^ Bujalski 2002, p. thirteen

- ^ Coules 1991, p. ix

- ^ a b Bujalski 2002, p. 14

- ^ Langford, David (Nov 22, 2017). "Uplift". In Clute, John; Langford, David; Nicholls, Peter; Sleight, Graham (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Gollancz.

For both the experimental mouse and the retarded narrator in Flowers for Algernon ... , the arc of uplifted intelligence rises high above the species norm into similarly lonely realms, only to autumn again.

- ^ Budrys, Algis (August 1966). "Milky way Bookshelf". Milky way Science Fiction. pp. 186–194.

- ^ Budrys, Algis (February 1967). "Galaxy Bookshelf". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 188–194.

- ^ "1967 Hugo Awards". TheHugoAwards.org. July 26, 2007. Retrieved April xxx, 2008.

- ^ Silverberg 1970, p. xii

- ^ "Daniel Keyes to exist Writer Emeritus". Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. Retrieved April 21, 2008.

- ^ Hill 2004, pp. 7–9

- ^ Jodi Mathews (June 22, 1999). "Controversial book removed from Texas heart school after one parent complains". firstamendmentcenter.org. Archived from the original on September 28, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2008.

- ^ Birdsall, Peter (1978). Heed War: Book Censorship in English Canada. CANLIT. p. 37. ISBN0-920566-01-4.

- ^ Dick, Judith (1982). Not in Our Schools? School Book Censorship in Canada: A Word Guide. Canadian Library Assn. p. 8. ISBN0-88802-162-3.

- ^ Tony Banks Biography, tonybanks-online.com

- ^ "Agenda / Holeulone". La Terrasse. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- ^ Beck, Marilyn; Smith, Stacy Jenel. "A Talk with 'The Simpsons' Al Jean on the Show's 25th Anniversary". creators.com. Archived from the original on October half-dozen, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ "It's Ever Sunny in Philadelphia" Flowers for Charlie (TV Episode 2013) , retrieved September 24, 2018

- ^ Iain Cameron Williams (2019). The Empirical Observations of Algernon. Vol. 1. i will publishing. ISBN978-1916146501.

- ^ The Empirical Observations of Algernon - Writer's Note, folio V mentions Flowers for Algernon being the inspiration behind the title of the book: https://b2l.bz/XKlHUM

- ^ a b c d e "Flowers for Algernon". Daniel Keyes. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ The 2 Worlds of Charlie Gordon at IMDb

- ^ Charly at IMDb

- ^ "Flowers for Algernon past David Rogers". Dramatic Publishing. Archived from the original on Oct 23, 2007. Retrieved Apr 23, 2008.

- ^ "Charlie and Algernon: volume and lyrics by David Rogers, music by Charles Strouse". Dramatic Publishing. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- ^ "Charlie and Algernon". Musical Notes. Retrieved Apr 24, 2008.

- ^ "Genesis News Com [it]: Tony Banks - A Curious Interview - 30th September 2009". www.genesis-news.com . Retrieved Baronial 20, 2019.

- ^ Coules 1991, p. xxiv.

Sources [edit]

- Bujalski, Andrew (2002). Aglietti, Boomie; Quinio, Dennis (eds.). Flowers for Algernon: Daniel Keyes. Spark. ISBN1-58663-514-X.

- Coules, Bert (1991). The Play of Daniel Keyes' Flowers for Algernon (including notes past Robert Chambers). Heinemann (published 1993). ISBN0-435-23293-2.

- Hill, Cheryl (2004). "A History of Daniel Keyes' Flowers for Algernon" (PDF). LIBR 548F: History of the Book. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 21, 2007.

- Keyes, Daniel (1999). Algernon, Charlie and I: A Author's Journey. Boca Raton, FL: Challcrest Press Books. ISBNane-929519-00-one.

- Scholes, Robert (1975). Structural Fabulation: An Essay on Fiction of the Future . Notre Matriarch, IN: University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN0-268-00570-ii.

- Silverberg, Robert, ed. (1970). The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One, 1929–1964. Tom Doherty Associates. ISBN0-7653-0537-2.

- "Flowers For Algernon". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction.

External links [edit]

- "Flowers for Algernon" (short story) title list at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- "Flowers for Algernon" (novel) title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- "Flowers for Algernon" on the Internet Annal

maynardsundis1937.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flowers_for_Algernon

0 Response to "Flowers for Agernon Why Did Charlie Become Dumb Again"

Postar um comentário